Last week, my dad called me because he was having trouble logging in to his online investment account. I had been in the middle of editing something when the call came in, and I looked down at my phone with trepidation. His face looked back up at me in a photo recent enough to capture his unraveling. His cottony hair stood on end. His eyeglasses sat askew on his nose. His brow was furrowed, his face unshaven, and his eyes were glued to the bottom of his screen. He had the visage of someone in deep concentration to take what, for many of us, would have been a simple selfie. Seeing his image made my jaw clamp down.

I took a deep breath and waited a full three rings.

Every family has its tech-support genius, and ever since I learned to connect the VCR to the television back in 1985, that genius has been me. Earlier in the summer, my dad received the surprising (and in hindsight not so surprising) diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Dementia, and his cognitive capacities had declined in specific ways. Technology, his former good buddy, had become a vexing adversary.

"Hi dad," I answered. "How's it going?"

“Not great,” came the answer, along with a litany of weary complaints. The weather had turned gray. Mom missed the dog. He wanted to drive a car. A jackhammer outside was shattering his concentration, and he needed help logging in to his investment account.

Genius that I am, I had set up his iPad so that he could log in to his accounts using his fingerprint, so I reminded him to rotate his iPad vertically and use the pointer finger of his right hand and lay (not press) the button at the bottom of the device.

"Okay," he said, searching. "They keep changing where they put the button, so I don't know. Is it this one?" he asks.

"I can't see your screen," I remind him. "It's the button that's built into the device," I said. "It's black and sort of indented. You'll find it at the very bottom of the device."

"Hang on," he said. I waited while he set the phone on the table and scrutinized the iPad. I could hear the jackhammer in the background. I put the phone on speaker and shifted my focus back to my work at hand.

“Dammit," he mumbled. Do you hear that?"

I'm tempted to bore you with the details of my phone support, but I'll just say we spent three hours over three successive days trying (unsuccessfully) to login to his investment account. On that first day we tried FaceTiming. We tried feeling the screen for indents. We tried looking for the color black. With each passing minute, each possible solution crumbled to dust and a surge of hot energy rose through my body. By 90 minutes, I wanted to rip my phone in half. My voice rose in volume. "I can't help you with this stuff remotely, dad. I can't help you. I just can't.” I almost hung up on him.

I wanted to rip my phone in half.

That night, I sat down to read a recent New Yorker essay by David Sedaris about his neighbor's sheep. Sedaris lives in the English countryside in what I picture to be a comely stone house. Across the lane from his house lives a shepherd, who tends a flock of ewes and lambs. And in the field behind Sedaris’s house, the shepherd keeps the rams, who are (by no fault of their own) complete assholes.

Sedaris is a humor writer, but this essay veered into dark and resonant territory. Sedaris described how one day, a five-month-old male lamb was separated from his mother across the street and relocated to the ram pasture behind his house. Soon after, the ram lamb began calling for his mother. "His voice sounded almost human,” writes Sedaris. “Mommy!” bleats the ram. “Son!” bleats the ewe.

Sedaris finds the situation personally distressing. It brings up his own childhood memories of longing, fear, and shattered trust. He remembers the sense of disbelief that came when his cries for help went unanswered and no one came to save him (from summer camp). His partner Hugh suffered a deeper estrangement when his father took a posting in Mogadishu and the family left him in Ethiopia, at fourteen, “wondering how those who supposedly loved him could possibly have allowed this to happen.”

I wondered how many people in the world right now were asking the same question? How did we allow the wars in Ukraine and Israel/Gaza to escalate so quickly? How did we let our carbon emissions spiral out of control? How did we fail to anticipate the aging, illness, and death of our parents?

Sedaris endures a long night listening to the ram and his mother bleat back and forth. "At three-thirty, I wondered if I could possibly carry the ram lamb back across the lane—if I could enter our pasture without getting butted by Igor [the alpha ram]—and at four I was, like, “O.K., you have to shut the fuck up now. Both of you. I mean it.”

This was meant to be the punchline, but it felt wrong to laugh. Surely, when confronted with our own impotence, we can do better.

Surely, when confronted with our own impotence, we can do better.

"Your mom and dad are your spiritual practice," said my counselor, Evan. I spoke with him in the morning before the second tech-support call with my dad. "They will show you all the ways you lack patience."

This wasn’t what I wanted to hear. I asked Evan why I should try to be patient when the house is burning down. My dad's insatiable curiosity, sound reasoning, and good humor were bleaching like coral before my eyes. Shouldn't I find a way to stop it? Shouldn't I do something?

“If you want to protect yourself from anger and cynicism,” said Evan. “You must learn to be helplessly helpful."

I wrote down his words but couldn’t quite swallow them. I didn’t want to be helplessly helpful. I wanted to be actually helpful.

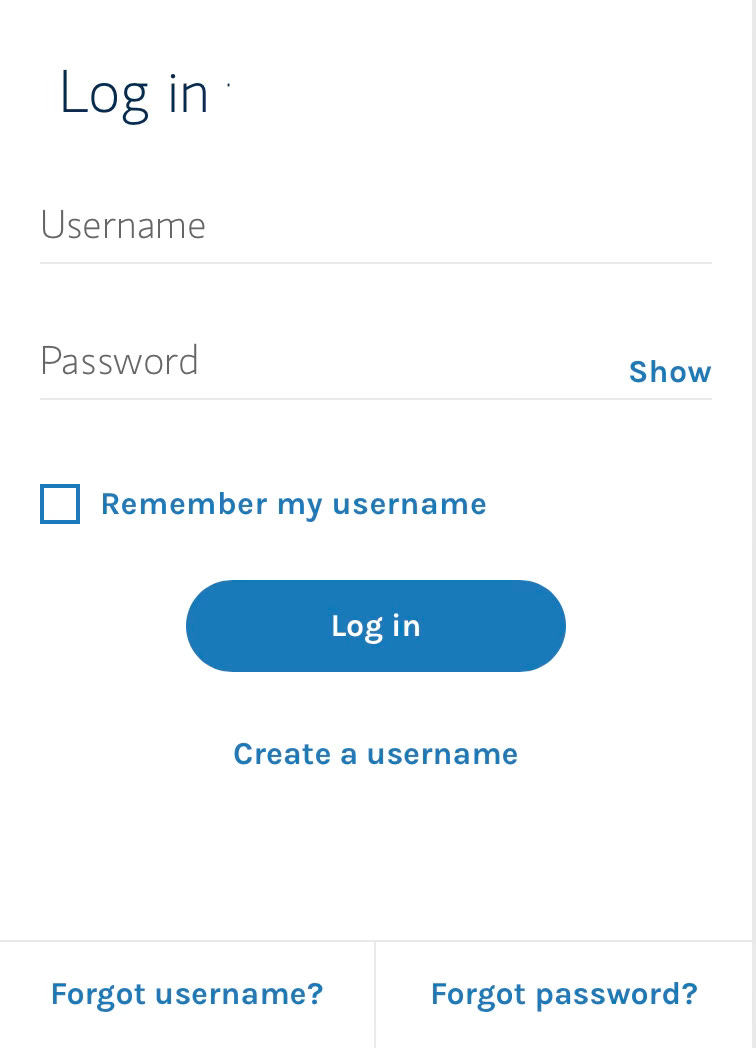

On the second day, my dad called announcing that he had found the button and was ready to try again, but by then the fingerprint ID function had been deactivated. I tried to walk him through typing his login ID and password, but his big fingers and those tricky capital letters and symbols proved too difficult. The site locked him out.

I wasn’t angry with him, per se. He was trying to follow my directions, eager to push the right buttons and find the right keys. He couldn’t understand why everything had become so hard. Why he couldn’t drive. Why he and my mom couldn’t live on Whidbey Island with their dog. Why he couldn’t go out and get a Yogachino at his favorite drive-through coffee place any time he wanted. Why he couldn’t fly to California in the winter. Couldn’t remember words. Couldn’t control his hands. Couldn’t login to his investment account.

On the third day of tech support, my dad and I spent the hour discussing why he needed to see his investment account in the first place. We had just gone through these accounts together over Thanksgiving and I'd be returning to Seattle in a few days. Was there an urgent question he needed answered?

"I just want to be able to log in to my own investment account," he said, nearly weeping with frustration.

"I get it," I said, sitting back in my chair. I turned on FaceTime so we could see each other’s faces and spent the hour listening to the same stories of frustration I'd been hearing since the summer. "You're hitting a lot of walls. I understand how frustrating that would be. I'm sorry. It's been a hard year."

I continued to listen, but the more he spoke about the things he couldn’t do, the places he couldn’t go, the people he couldn’t trust, the more I began to feel blamed. Like I was doing a bad job helping him. Like his litany of problems were my fault. Instead of listening, I grew angrier. “O.K., you have to shut the fuck up now.” I have my own family to take care of, my own bills to pay, my own job to do.

Evan explained that anger can stem from an inability to accept the realities of a situation. If I could accept the reality of my dad’s dementia, for example, I could stop trying to help him log into the investment account and help him look for better ways to spend his precious time.

“Like painting,” I suggested to my dad a few days later.

But my dad bristled and told me he doesn't want to look for something else to do. He doesn’t want to be told what to do. He wants to keep track of his assets. He wants to drive, book a plane ticket to California, eat out if he feels like it. “I don’t want to live the rest of my life watching television in a retirement home,” he said to me when I visited him a few days ago, wringing his hands as he walked beside me. “I want to live.”

“Waking up and getting pissed off at your iPad is not living,” I retorted.

We ended the discussion in a stalemate.

I’m learning that I can’t fix my dad’s life like a VCR. I can’t make all his problems go away. I can’t alleviate all his suffering. I can’t stop technology from cruelly robbing him of his autonomy. And maybe that’s not my job, anyway.

Maybe all I can do is accept my own helplessness.

And offer it helpfully.

Keep storytelling its balm for my soul

This was really fantastic and completely relatable. When my Dad was declining with dementia, I had to deal with that exact same log in screen many times. Luckily he was only 10 minutes away and I could resolve the problem more easily. Some of my best memories of my Dad are the time I spent with him during his final 2-3 years: all the challenges of helping him with trivial tasks, listening to his delusional stories, being disowned several times, and his frustrations about losing his independence. Great story! And always happy to commiserate if that helps. 🙂